New Urbanist Blacksburg

by Max Rooke & Lonnie Hamilton III

Farmland Conservation

Priority: High | Cost: Low | Implementation: Short

Both town residents and returning Hokies can agree on an image of Blacksburg as a small, idyllic town nestled between mountains and surrounded by rolling green farmland. A drive around town provides pastoral scenery of family farms, hay bales, and grazing cattle. However, as demand for housing near Virginia Tech continues to grow, the agricultural heritage of Blacksburg and Montgomery County is threatened by increased development. Farmland is vital for both rural and urban economies, with around ¼ of all farmland located within a metropolitan area, and the New River Valley's Blacksburg-Christiansburg-Radford Metropolitan Area is no exception (Dillemuth, 2017). Not only is agriculture (specifically beef and forestry) the largest and oldest industry in the New River Valley region, but it also supports the local food system that allows consumers to reduce the carbon footprint produced by food production and transportation (New River Valley Regional Commission, n.d.).

Image by Lonnie Hamilton

Source: Town of Blacksburg

Source: Glad Road Growing

Image by Lonnie Hamilton

Open agricultural areas provide a host of benefits to the local community, often called “rural amenities,” which can include a variety of non-monetary value additions. Farmland is not well-protected by the free market because rural amenities, (ecosystem services, food security, wildlife habitat, aesthetic appeal, and agrarian cultural heritage) do not have monetary value (Hellerstein et al., 2010). It is impossible to monetize the value of a scenic drive near town, just as it is impossible to appraise the effect of open greenspace on local waterways. However, as soon as farmland is developed, it loses its monetary value as productive agricultural land as well as its ecological and aesthetic value immediately and permanently (Dillemuth, 2017). Therefore, as urban development expands into current agricultural and open space areas, intervention from the town government is needed to ensure that Blacksburg continues to reap the ecological and social amenities provided by its extensive rural surroundings. Municipalities across the country have approached farmland conservation from a variety of angles, with different regions having different values at the forefront of conservation efforts. An analysis of current legislation by the USDA Economic Research Service suggests that preserving open green space, pastoral beauty, and agrarian cultural heritage are primary concerns at the heart of most legislation. However, the more densely populated regions such as the Northeast are often concerned with protecting the widest variety of rural amenities, while sparsely populated regions such as the Midwest indicate more focused concern on the purely economic aspects of farmland transition (Hellerstein et al., 2010). Regardless, most previous municipal efforts towards agricultural land preservation have seen bipartisan support and been widely well-received by the public (Schneider, 2006).

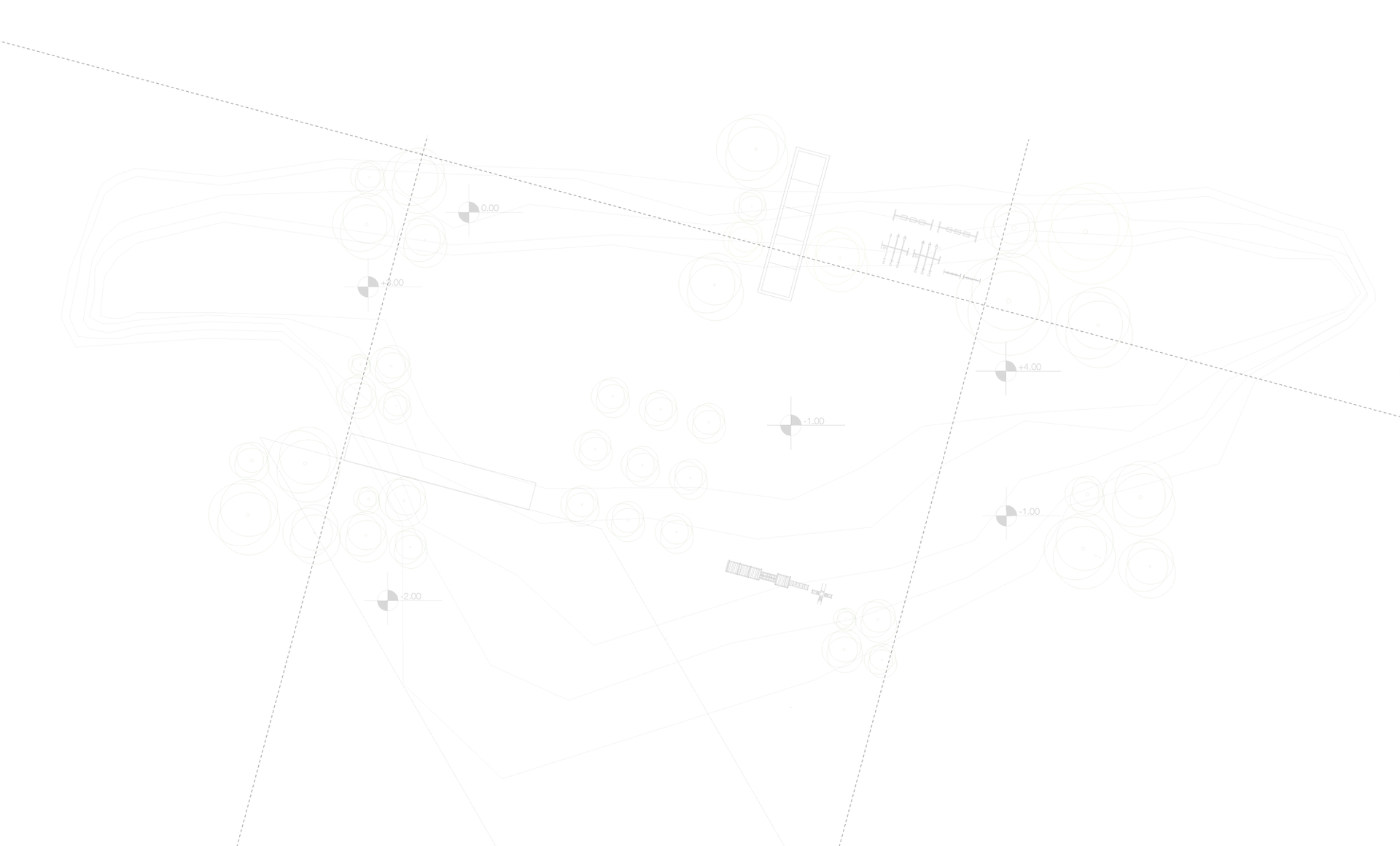

The first effort towards farmland conservation that Blacksburg needs to make is to create an agricultural conservation zoning district to identify and administer to existing farmland. Agricultural conservation zoning can be used to restrict allowable development density to discourage residential conversion through several approaches. Requiring large minimum lot sizes, area-based building allowance formulas based on percentage of parcel, or sliding scale formulas where the number of dwelling units allowed is determined as a ratio to the total farm area have all proven to be effective in combating development, especially for areas like Blacksburg where productive farmland is usually sold to be subdivided into housing units (Dillemuth, 2017). The above maps show Blacksburg's current zoning districts and the recommended farmland conservation overlay district. Currently, most of the target area is zoned RR-1, which allows for development with up to one dwelling unit per acre intermixed with agricultural use despite the comprehensive plan’s objective of preserving this open space (Town of Blacksburg, 2016). The ideal reaches of an agricultural conservation district would encompass all the agricultural and forestal districts (shown in green overlay) and all areas zoned RR-1 that would be compliant with the agricultural conservation district’s guidelines at the time of the rezoning. Density guidelines governing the district could be determined using any of the aforementioned strategies, but the district should also be barred from any further extension of town sewer or water systems.

Agricultural conservation zoning had seen some success in Virginia Beach, where the city enacted a green line to preserve the rural character of the southern reaches of the city as well as to minimize impervious surface cover in wetland areas (City of Virginia Beach, n.d.). Notably, this designation also prevented the extension of municipal water and sewer systems below the green line, allowing for the cost burden of extending sewer and water into parcels to fall onto the developer as an additional barrier to potential housing developments. By shifting this cost burden, cities like Virginia Beach can use funding for more aggressive approaches. In Virginia Beach, the green line was proven to be less effective as housing demand near rural amenities continued to rise, and the city transitioned to its current Agricultural Reserve Program. This program involves a tax credit given to farmers to dissuade them from selling their land to developers (City of Virginia Beach, n.d.). All in all, studies have found that while zoning to protect farmland is effective, the most effective strategy is to directly pay farmers to forever set aside their land as farmland (Schneider, 2006). In Blacksburg, this monetary incentive would best be implemented as the transfer of development rights or the complete buyout of development rights by the town. The transfer of development rights should be utilized first and most aggressively because it shifts the expenses associated with conservation from taxpayers to the private market. TDR programs allow development rights to be seperated from properties in the agricultural conservation district and be purchased by developers to allow denser development in target areas, such as those near the Virginia Tech campus. The complete purchase of development rights (PDR) works similarly, except the government purchases the development rights with municipal funding and then those development rights are made permanently unavailable (Dillemuth).

All together, the various systems can and should be utilized together in order to conserve Blacksburg’s farmland and rural amenities adequately and efficiently. An agricultural conservation district should be created to define the target area, and within that district landowners should have the opportunity to participate in TDR programs to further limit development. Furthermore, the Town of Blacksburg should enact a PDR program using Green New Deal funding to purchase outright the development rights to the highest priority parcels. These high priority parcels would include those with pre-existing commercial agricultural use as well as those within the district with significant stream coverage (shown in blue overlay on the above linked map) which would therefore benefit most from the ecosystem benefits provided by open space. Overall, this project would support the goals of the Green New Deal by preserving natural land that could continue to provide ecosystem services as well as encouraging local food systems and denser development, both lowering Blacksburg’s collective carbon footprint.